Language in Uniform: Teresita Eldredge Advances English Language Capacity for the Honduran National Police

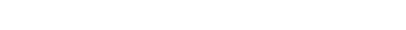

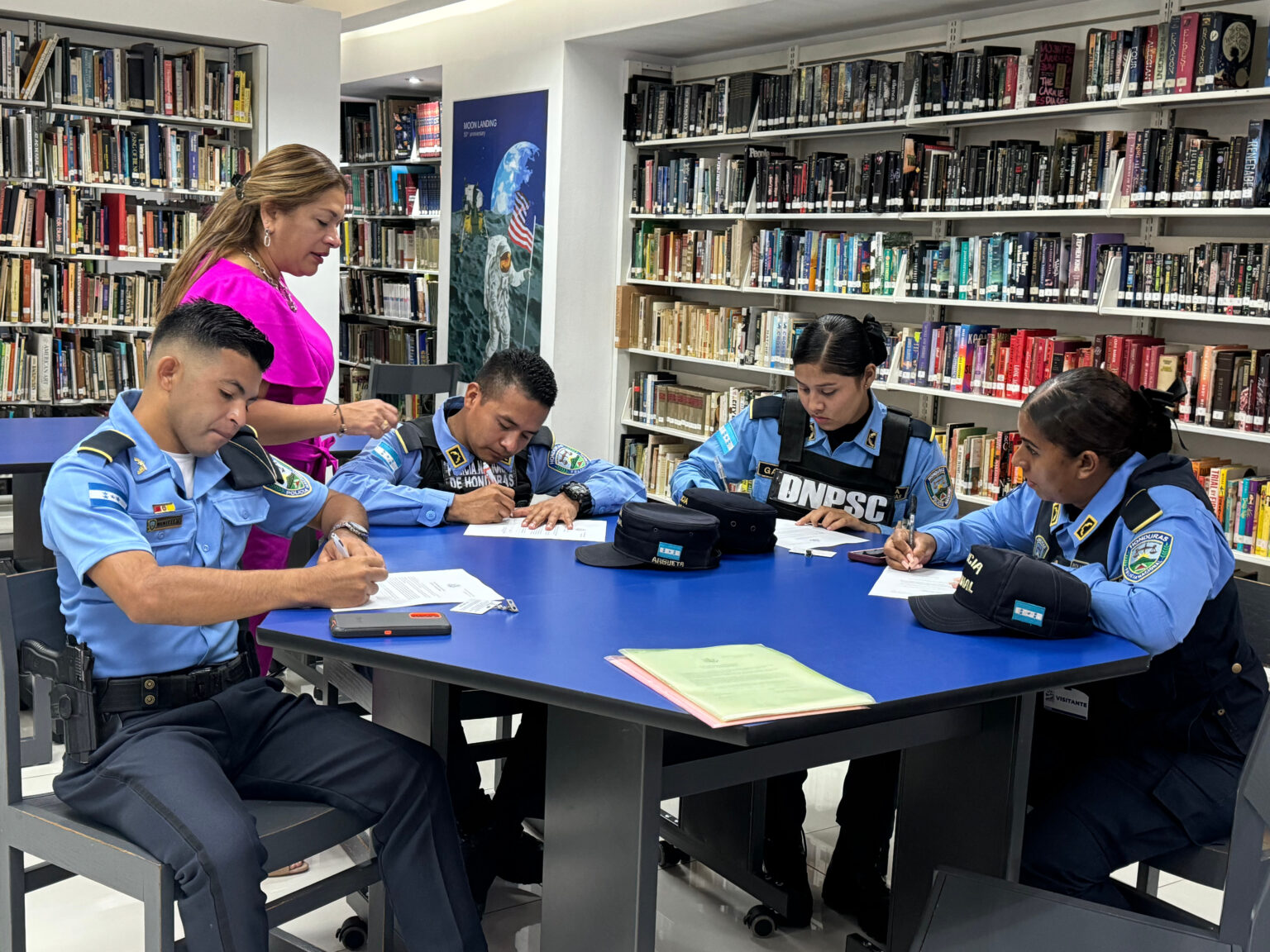

In Honduras, a newly developed English for Specific Purposes (ESP) curriculum is helping police officers build the foundational language skills they need to communicate with English-speaking residents and visitors. English Language Specialist Teresita J. Eldredge led the effort, working in close collaboration with binational centers in Tegucigalpa and San Pedro Sula to design a 40-week Level 1 course tailored to the specific duties of law enforcement personnel.

“This unique project will help advance U.S. foreign policy in Honduras and contribute significantly to the safety and welfare of English speakers living in and/or visiting the country,” Eldredge said. She adds that the project, which emphasized the use of police jargon in authentic language contexts, “could become a model for future U.S. missions around the globe.”

The project, launched in partnership with the U.S. Embassy’s International Narcotics and Law Enforcement (INL) Office, was implemented through the Public Affairs Section’s access to the Department of State’s English Language Programs. Officers participating in the course include those assigned to various policing functions and units nationwide.

Curriculum Grounded in Local Needs

Before designing the curriculum, Eldredge conducted a detailed needs assessment. She surveyed 169 police agents and interviewed 20 more from nine different Honduran police departments. She also held meetings with police commissioners, operational unit chiefs, and directors of the Honduran National Police University. These conversations provided insight into internal and external factors that could support or hinder learning, including work schedules, digital access, resources, and attitudes toward English.

She also assessed logistical and technical capacity at the binational centers, where approximately 60 officers per cohort would receive training. “For the successful implementation of a curriculum, it is imperative to learn the stakeholders’ capacity for supporting teachers and students,” Eldredge noted.

Meeting Officers Where They Are

One of the most significant findings of the assessment was that work shifts and schedule changes made regular attendance difficult. To ensure continuity, Eldredge developed interactive digital lessons combining instructions, media, and tasks that allow officers to engage with the material asynchronously.

Another recurring challenge was pronunciation. Many officers identified this as their greatest obstacle in speaking English. To address this, the first two units of the curriculum focus on vowel sounds and voice recognition activities, aiming to build confidence and accuracy in basic spoken English.

Building a Practical, Flexible Curriculum

Eldredge worked closely with the coordinators at the binational centers—meeting virtually for 6 to 10 hours each week—to co-develop the course. Together, they researched appropriate police vocabulary and identified authentic materials, including real Honduran police forms, to ensure that lessons reflected officers’ day-to-day responsibilities.

The curriculum includes language for common policing interactions, such as giving directions, taking reports, and delivering standard warnings. Officers are expected to become comfortable with key professional phrases, including the Miranda rights (“You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say can and will be used…”) so common in the American justice system.

Each unit ends with a Problem-Based Learning (PBL) task, where learners apply language skills to a realistic policing scenario. These tasks were designed to reinforce the course’s practical orientation and keep the training rooted in the agents’ professional contexts.

Computer-Assisted Language Learning (CALL) tools were also integrated into the curriculum to support independent study, enhance pronunciation, and increase learner engagement outside the classroom. By the end of the course, agents should be able to carry out the first minute of an English-language interaction with clarity and confidence.

Preparing for the Next Phase

Although the Level 1 curriculum is complete, the broader project continues. Phase II focuses on hiring and training instructors who will implement the course and expand the set of enhanced lessons. These teachers will be trained in using CALL tools and authentic resources to help officers build fluency and communicative competence.

“The task is unique and will demand teachers’ learning new approaches,” Eldredge said, “especially around CALL tools to foster fluency.”

A Bridge Beyond Language

Eldredge’s work also extended to professional development with the Centro Cultural Sampedrano in San Pedro Sula, where she led workshops on integrating CALL tools across different learning contexts. While the curriculum emphasized language acquisition, it also opened the door to cultural exchange.

“Having direct interaction and exposure to different products, practices, and perspectives enriches our appreciation of our own language and culture,” she said. “Despite differences, fundamental human values are the same. In essence, cultural exchange allows individual growth, connects, and enriches global society.”

Wider Impact and Recognition

For Regional English Language Officer Russell Barczyk, who oversaw the first phase of the project, Eldredge’s impact was both immediate and far-reaching:

“It was fantastic to have a Specialist work so well with this host institution, the Honduran police, and meet local and State Department goals. I know that staff at the Embassy appreciated Teresita’s professionalism and that her work shows a clear path to making a real difference in the English proficiency of security personnel. As RELO, I appreciated Teresita’s willingness to share her work and experience with other Fellows and Specialists working in this sector to have a bigger impact in the region.”

Indeed, this project exemplifies the power of English language programming as a tool for diplomacy, capacity-building, and mutual understanding. Through her work, Eldredge has not only developed a practical curriculum but also strengthened the connective tissue between communities, cultures, and institutions.

About Teresita J. Eldredge

Teresita Juliet Eldredge holds graduate degrees in Applied Linguistics and Educational Leadership. She is currently the Supervisor of World Languages for Jersey City Public Schools and a part-time lecturer at Rutgers University-Newark, where she helped develop the ESL and Bilingual Teacher Certification Program. A former Fulbright scholar and returning English Language Specialist, her experience spans continents and contexts—from Peru to Uzbekistan to China—with a focus on language equity, teacher training, and multilingualism. Her article “The Power in Language Education as Critical Pedagogy: Changing the Multilingualism Mindset” was published in WATESOL in the spring of 2024.